Identifier: TRR260101.

Summary

RedKitten is a newly identified campaign targeting Iranian interests, likely including non-governmental organizations and individuals involved in documenting recent human rights abuses, first observed in early January 2026. The malware relies on GitHub and Google Drive for configuration and modular payload retrieval, and uses Telegram for command and control.

This activity appears aligned with the “Dey 1404 Protests”, a wave of intense civil unrest in Iran that began in late December 2025, following widespread economic strikes in Tehran. The protests were met with a deadly crackdown involving mass arrests and extensive civilian casualties. We assess that the threat actor rapidly built this campaign using AI tools, as indicated by multiple traces of LLM-assisted development.

While we could not reliably attribute this activity to an identified threat actor, we observed the use of techniques known to have been previously utilized by Iranian state-sponsored attackers alongside linguistic indicators, and we are confident that the activity originates from a threat actor aligned with the Iranian’s government security interests. We currently track this cluster of activity as RedKitten.

📑

Background: Iran efforts in suppressing the 2025-2026 protests

In an effort to suppress information flow around the Dey 1404 protests and subsequent massacres, the regime enforced recurring internet blackouts to hinder documentation of abuses and disrupt civilian coordination. At the same time, Iran’s leadership faced growing external pressure, particularly from the United States (U.S.) which warned of possible intervention, should the regime attempt to violently repress the protests and if a nuclear deal could not be met. The U.S. deployed an aircraft carrier strike group as part of this coercive signaling.

As more details of the violent repression emerged, threat actors appear to have exploited the staggering human toll to target organizations or individuals seeking information about the deadly crackdown. This modus operandi is consistent with past Iranian state-linked campaigns, which have frequently combined crisis-driven lures, such as the October 7 attacks in Israel.

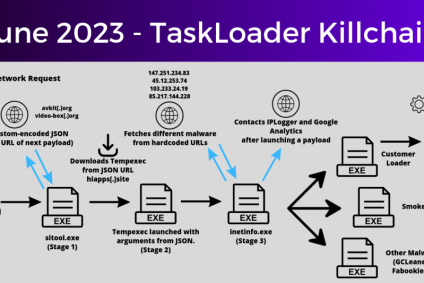

Infection chain

We identified a 7z archive uploaded on January 23, 2026 to an online multiscanner with the following filename in Farsi: فایل های پزشکی قانونی تهران(1).7z (translated: Tehran Forensic Medical Files).

| Filename | فایل های پزشکی قانونی تهران(1).7z |

| File type | 7z archive |

| Creation time | 2026-01-22 22:41:27 |

| Hash (SHA-256) | 8c0d75a043fa81d9600596f5dda8396856b5b6660908a0e60b699721e087d541 |

The archive contains 5 macro-enabled Excel spreadsheets (XLSM), supposedly parts one to five of a list of individuals from Tehran who died between December 22, 2025 and January 20, 2026 (Dey 1404 in the Persian calendar).

Weaponized XLSM documents

Decoy content

These files, named for example Final List_Victims_D_1404_Tehran_Part one.xlsm (translated from لیست نهایی_جانباختگان_دی_1404_تهران_بخش اول.xlsm), most likely refer to the reported executions and the massacre of protesters who rose up against the Iranian Ayatollah regime.

| SHA-256 hash | Filename |

|---|---|

d3bb28307d11214867c570fe594f773ba90195ed22b834bad038b62bf75a4192 |

لیست نهایی_جانباختگان_دی_1404_تهران_بخش اول.xlsm1 |

90aebc9849b659515fd70dde6db717ad457ab2a90522a410d1fd531ca8640624 |

لیست نهایی_جانباختگان_دی_1404_تهران_بخش دوم.xlsm2 |

96ee9d3ed80c59c4bf39ed630efbfa53591fbe51155db7919ef64535a6171044 |

لیست نهایی_جانباختگان_دی_1404_تهران_بخش سوم.xlsm3 |

c40c94d787f6a35ac1cb4c5f031cf5777b77c79dc3929181badea33aaf177aa7 |

لیست نهایی_جانباختگان_دی_1404_تهران_بخش پنجم.xlsm4 |

59ee007fd17280470724eb8a11ab12a98e85fd2383af3065f5f09a7e1a73f88c |

لیست نهایی_جانباختگان_دی_1404_تهران_بخش چهارم.xlsm5] |

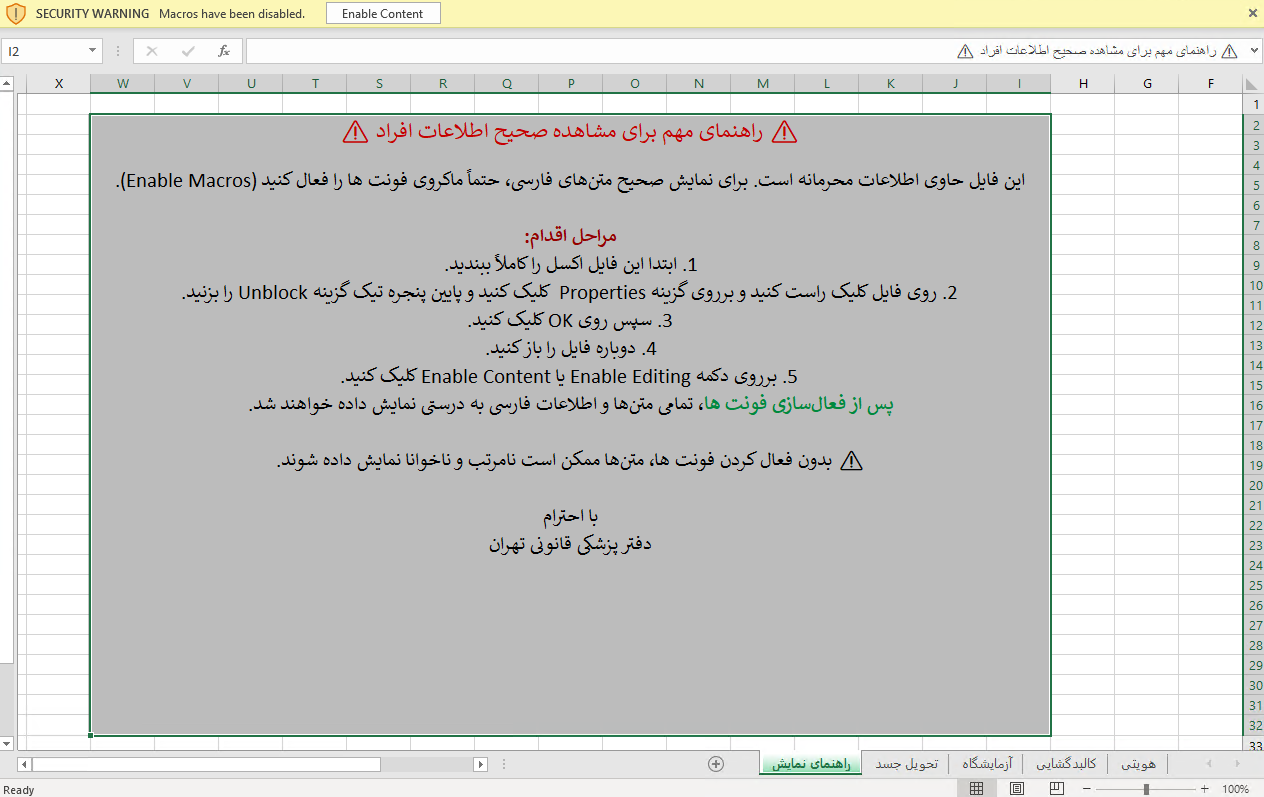

The XLSM files all contain malicious VBA macros and identical lures.

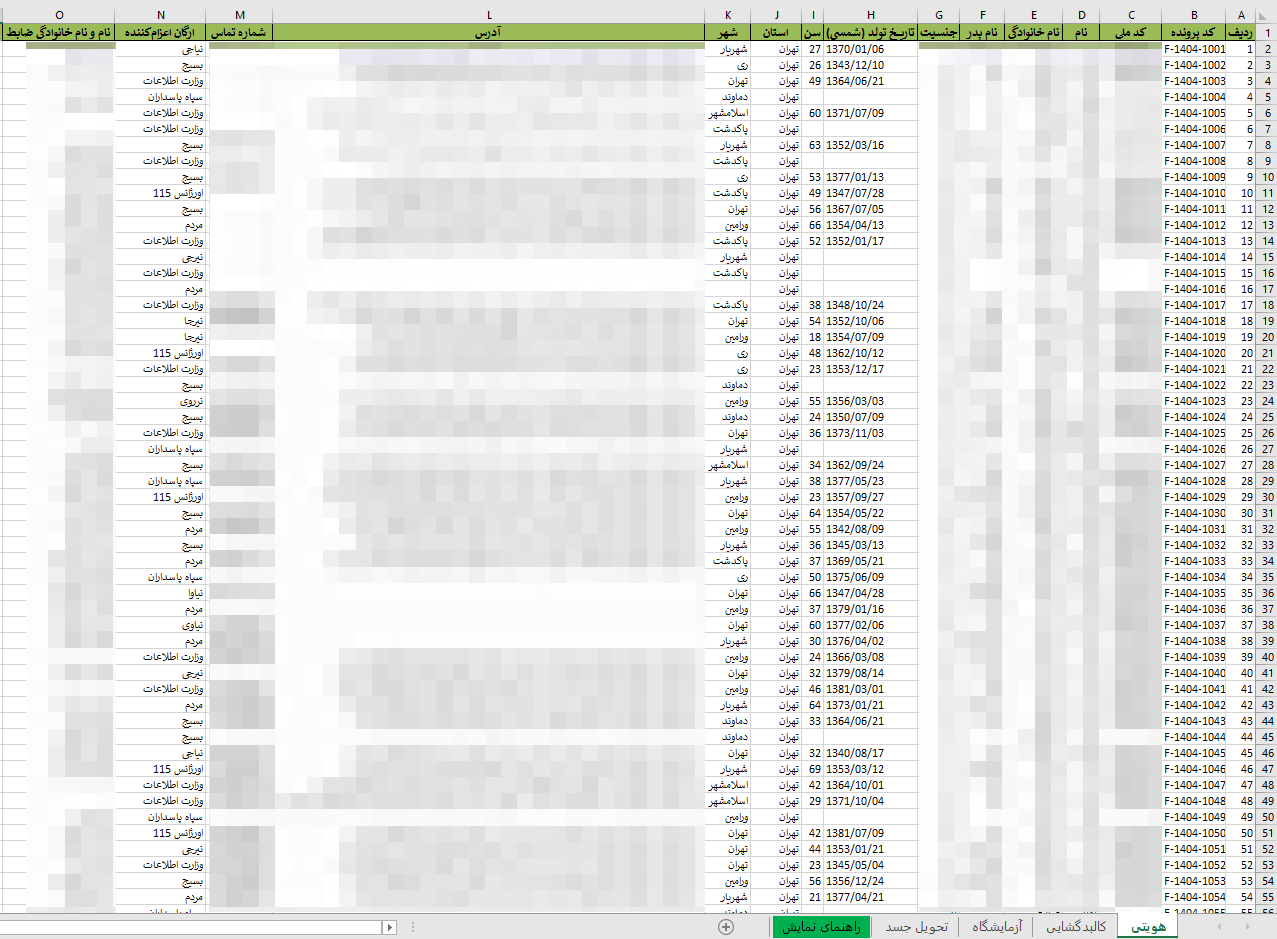

The lure is composed of 5 sheets written in Farsi, listing a supposedly confidential database of 200 bodies processed during the aforementioned time period.

| Sheet original (Persian) name | English Translation |

|---|---|

| هویتی | Identity / Identification |

| کالبدگشایی | Autopsy / Dissection |

| آزمایشگاه | Laboratory |

| تحویل جسد | Body Delivery / Release |

| راهنمای نمایش | Display Guide / Help |

The “Identify/Identification” sheet lists deceased individuals, their PII (Personally Identifiable Information) and the referring organization, as well as officer name. Among the organizations listed are:

- Basij (paramilitary volunteer militia);

- Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS);

- IRGC (Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps);

- Emergency services (i.e. ambulance);

- Public (implying a body found by citizens).

The “Autopsy” sheet details the time and cause of death, the appointed doctor and any special remarks (the contents of this sheet are graphic and disturbing). Toxicology and narcotic test results are provided in the “Laboratory” sheet, listing some individuals being slightly under the influence of alcohol. The “Body release” provides the casualties release date and the person (family member) to whom they were released to. Finally, the “Help” sheet entices the user to click the “Enable Content” or “Enable Editing” button in order to allow the macros to run.

We assess that this document is a forged ‘shock lure’ designed to target organizations or individuals seeking information about missing persons or political dissidents. Several internal inconsistencies indicate the data is fabricated: most notably, the mismatch between birth dates and ages. Furthermore, the document lists implausible workload for a small group of doctors over a very short period. And while the file omits important data, such as the addresses of the family members, it provides an unnatural level of detail regarding the causes of death and the specific security agencies involved.

This tactical reliance on high shock value aligns with Iranian-nexus campaigns, such as the one we previously reported.

VBA Dropper

Each XLSM file contains the same VBA macro, which acts as a dropper for a C# implant. Upon execution, it extracts the Base64-encoded C# source code and .NET application configuration files which are stored in in the custom XML parts of the document. The source code is written to a temporary file in %TEMP% using a random name with the extension .cs (e.g. ~radFAC27.tmp.cs). A first configuration file is written to %LOCALAPPDATA%\WindowsMediaSync, alongside a legitimate binary, AppVStreamingUX.exe, copied over from C:\Windows\Sysnative\AppV\ or C:\Windows\System32\AppV\.

The dropper then invokes the host’s .NET C# compiler to generate a DLL AppVStreamingUX_Multi_User.dll in %LOCALAPPDATA%\WindowsMediaSync (remark: a compile log file is written to %USERPROFILE%\Desktop\compile_log.txt).

Note that in case the AppVStreamingUX.exe binary could not be copied to %LOCALAPPDATA%\WindowsMediaSync, the dropper copies dfsvc.exe from %SYSTEMROOT%\Microsoft.NET\Framework\v4.0.30319\ instead, and writes a second .NET application configuration file previously extracted to the same target directory.

Both configuration files require the legitimate process to load the AppVStreamingUX_Multi_User assembly located alongside the executable, and to instantiate the AppVStreamingUXMainOff AppDomainManager class, resulting in the actual implant being loaded. This technique is known as “AppDomainManager injection”.

The execution is triggered by a scheduled task (named MediaSyncTask followed by a random number between 100 and 999, e.g. MediaSyncTask276) which runs the target binary one minute after being enabled.

The overall style of the VBA code, the variable names and methods it used, as well as comments left in it (e.g. --- PART 5: Report the result and schedule if successful ---) indicates that it was very likely and at least partially AI-generated.

C# implant: SloppyMIO

The deployed implant we dubbed SloppyMIO (AppVStreamingUX_Multi_User.dll) is not compiled in a deterministic way, resulting in different binaries for each compilation.

It retrieves its configuration steganographically from images whose URLs are obtained via a Dead Drop Resolver (DDR) backed by GitHub. From these images, it extracts a XOR key, Telegram bot token and chat ID, and module URLs from an LSB-hidden payload (details below).

The malware can fetch and cache multiple modules from remote storage, run arbitrary commands, collect and exfiltrate files and deploy further malware with persistence via scheduled tasks. SloppyMIO beacons status messages, polls for commands and sends exfiltrated files over to a specified operator leveraging the Telegram Bot API for command-and-control.

The following sections cover the configuration extraction, the available modules as well as aspects related to the C2 communication, leaving a few peculiarities aside.

Configuration

The configuration is stored in image files similar to the one displayed hereafter and retrieved from URLs provided by a GitHub Gist.

SloppyMIO leverages Least-Significant Bit (LSB) steganography to conceal the configuration within the image. It first checks the retrieved image file to make sure that it is large enough to contain a payload length encoded on 32 bits. For each pixel, it extracts the LSB of the current channel before incrementing the channel index. Channels are incremented from 0 to 2, following the RGB – Red, Green and Blue – order. This process allows to produce a bit stream with the following pattern (with R, G, B respectively designating the Red, Green and Blue channels, and the digit indicating the current pixel index): R0, G0, B0, R1, G1, B1, R2, G2, B2, [...].

This bit stream is then converted to an integer value which is the expected payload length. The latter is being checked so that it is positive and does not exceed 5,242,880 bytes (which may be related to an old file size limit for the Telegram Bot API).

Then, the implants proceeds to the payload retrieval, performing an LSB extraction 8 times the number of bytes of the payload.

The extracted configuration is a made of a list of key-value pairs separated by a |, and formatted as follows:

xor=<value>|tel=<value>|chat=<value>|m1=<value>|m2=<value>|m3=<value>|m4=<value>|m5=<value>Each value is Base64 and XOR-decoded using the provided key (xor being the only value which is simply Base64-encoded). Based on the previous example, the implant configuration is the following:

tel: Telegram API token;chat: Telegram chat ID;m1,m2,m3,m4,m5: URLs to retrieve modules 1 to 5 (see section Modules).

Every 10 loop iterations, SloppyMIO attempts to refresh its configuration by retrieving the contents of the GitHub Gist providing the image download URL.

Modules

SloppyMIO has the ability to retrieve and execute different modules from a repository (in our case, Google Drive). The analyzed sample’s configuration implementation suggests that it could support 10 specific modules, although the download implementation handles the retrieval of 5 modules.

The implant provides a caching mechanism for the modules in order not to require a new download each time an operator wants to run one of them. The downloaded modules remain available from the cache during 60 minutes after their compilation or last execution time. The cache is updated each time a module has to be run, and outdated modules are removed prior to running the target module. This results in the latter being downloaded again if it has not been used within the past 60 minutes.

The modules can be distributed as text files containing the Base64 and XOR-encoded C# source code of the module, or as already compiled DLLs. SloppyMIO relies on the document file name extension to make the distinction between these 2 cases (.cs or .dll). If a module is downloaded as source code, it is compiled to produce an in-memory assembly. Prior to adding it to the list of cached modules, the implant checks for the presence of a public static Run() method which is to be invoked upon module execution.

The analyzed sample supports the following modules:

cm: execute arbitrary commands viacmd.exe;do: collect files on the compromised host (path provided as a parameter). A ZIP archive is created for each collected file, taking into account the Telegram API file size limits. In the module we analyzed, 2 concurrent threads are used to proceed to the upload;up: write a file to%LOCALAPPDATA%\Microsoft\CLR_v4.0_32\NativeImages\. The file’s data is encoded within an image retrieved via the Telegram API. In this case, the relevant data is encoded within the blue channel of each pixel. Once retrieved, from top to bottom and right to left, the data stores the following information:- the file length, encoded using the first 4 bytes;

- the file extension, encoded using the next 10 bytes;

- the file’s content, starting from byte 14.

pr: create a scheduled task (Enterprise Workstation Health Monitoring) using the TaskScheduler COM interface in order to run an executable which path is provided as a parameter every 2 hours;ra: start a process by providing an executable file path and optional parameters.

Note that when SloppyMIO is loaded, it downloads and runs the pr module in order to setup persistence for the executable associated with its host process before entering an infinite loop, expecting commands from the operators.

C2 communication

Beaconing mechanism

Upon execution, SloppyMIO signals that it is available by sending the [<id>] - is online -- <date-time> message via the Telegram bot to the configured Telegram chat id, where <id> consists of the compromised machine name, the current user name, and the first 6 characters of a generated unique identifier concatenated with _ acting as a separator: <MACHINE-NAME>_<user-name>_<first-6-characters-of-a-generated-uid>.

Throughout its execution, the implant signals its availability by sending a [<id>] - is online <sleep-time> -- <date-time> message via the Telegram bot, where <sleep-time> is the duration it will remain idle, in milliseconds.

Receiving commands

SloppyMIO regularly attempts to retrieve an update from the Telegram bot. After each received update, it will sleep between 5 seconds and 1 minute before attempting to retrieve another update. If no update could be retrieved, the implant sleeps between 1 and 15 minutes before querying the bot for an update.

If an update message contains a document or photo accompanied with a caption, SloppyMIO checks if the latter contains the dllexec string pattern. In such case, it processes the document in order to retrieve a module (either a C# source code file or a compiled DLL) to execute. If the message’s caption does not contain dllexec, it proceeds to running the up module in order to upload a file to the compromised system. Note that the implant does not check for the presence of the up command in the caption.

If the retrieved message does not contain any document or photo, but does contain text, the latter is being processed as an input command by the implant. The following string commands are expected (provided hereafter in lowercase as the comparison is not case-sensitive):

download: will run thedomodule, which allows to download one or several file(s) from the compromised system;cmd: to run thecmmodule which allows arbitrary command execution;runapp: to start a process (see Modules section).

Data is sent back to the C2 server via the Telegram bot messages themselves, or via documents (with test.txt as a filename) if the size of the data exceeds 50000 bytes.

Note that for each action or command, SloppyMIO checks that the received document caption or message text starts with the [<id>] string pattern.

Implant process termination

When the user logs off or shuts down the compromised host, SloppyMIO sends a [<id>] - End With:<session-ending-reason> -- <date-time> message to the Telegram bot, where <session-ending-reason> specifies either a log off or a system shutdown.

Infrastructure

The threat actor relied on legitimate services to host its malware modules (Google Drive), act as a Dead Drop Resolver (GitHub), and provide a C2 channel (Telegram). While this somewhat limits our ability to pivot and discover additional, related infrastructure, it still divulges some useful information.

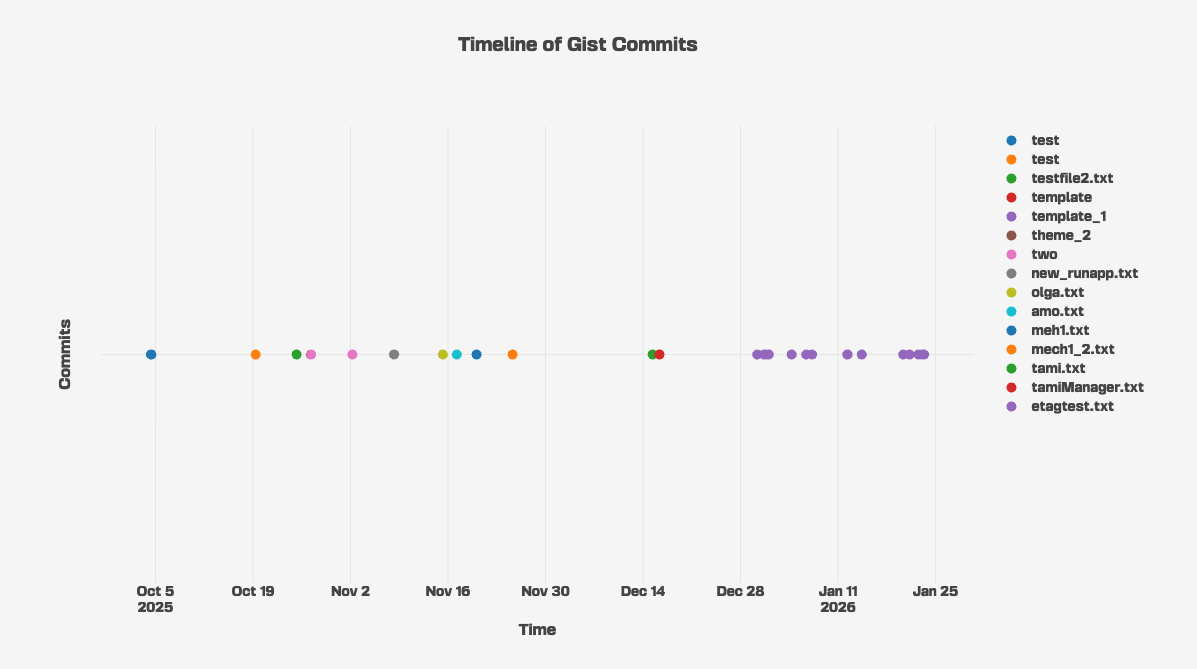

The GitHub account that is used for this campaign, johnpeterson1304 (johnpeterson202024@proton.me), was registered on September 20, 2025. It does not host any public repositories, but published 15 Gists, dating back to October 4, 2025. These Gists and their revisions show his progress developing SloppyMIO, with 9 different versions of the steganographic configuration image. The malware developer introduced an additional module over time, but mostly made changes to the Telegram bot configuration data.

Below is a complete timeline of the malware developer GitHub Gist commits, spanning from October 4, 2025 to January 23, 2026:

We suspect that the Google accounts used to host the modules and the steganographic image were most likely stolen. The malware developer used a total of two accounts, and for one of them we could find a legitimate owner.

Telegram bots and accounts

We observed a total of 9 variations of configuration data implanted into the same AI-generated kittens image, dating from October 4, 2025 to December 16, 2025. We also discovered a total of 13 Telegram bots, operated by 7 accounts. One of the accounts, named “Mech-One” had its language set to Farsi ("language_code":"fa").

Monitoring the bots’ activity, we were able to catch commands sent to a few infected hosts. However, it appears that these compromised hosts were running in sandbox environments. The Telegram bots are configured to send the command results back to the operators’ respective Telegram accounts, preventing us from catching the responses.

Nevertheless, knowing the operators’ Telegram accounts, we could filter for commands sent by them. The commands seen on January 26, 2026 are listed below:

| Time (GMT) | Victim ID | Command |

|---|---|---|

| 14:39:14 | cd81b9 | tasklist |

| 14:42:06 | cd81b9 | ipconfig |

| 14:43:42 | cd81b9 | dir C:\ |

| 14:44:44 | cd81b9 | tasklist |

| 14:48:03 | cd81b9 | tasklist |

| 16:22:27 | 484c8c | tasklist |

| 16:33:28 | a5f879 | wmic computersystem get model,manufacturer |

| 16:33:50 | 484c8c | whoami |

| 16:34:15 | a5f879 | wmic computersystem get model,manufacturer |

| 16:34:16 | a5f879 | wmic computersystem get model,manufacturer |

| 16:34:32 | 484c8c | whoami |

| 16:34:39 | a5f879 | wmic computersystem get model,manufacturer |

| 16:35:33 | a5f879 | wmic logicaldisk get name,size,freespace,filesystem |

Note that bots could be hijacked to receive commands from third parties, but they submit the results only to the configured Telegram accounts.

Targets

The malicious samples were uploaded from the Netherlands to an online multiscanner on January 23, 2026. At the time of writing, we cannot confirm if the uploader was an intended target or a researcher. Monitoring the bot commands, we only observed malware check-ins coming from sandbox environments.

We believe that non-governmental organizations and individuals involved in documenting recent human rights violations, as well as the horrendous level of violence demonstrated by the Iranian regime towards protesters, may be the intended targets of this campaign.

Attribution: it’s a kitten, but which one?

The observed infection chain shows overlaps with the Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs) of the Iranian, IRGC-aligned threat actor “Yellow Liderc” (a.k.a. IMPERIAL KITTEN, TA456). Notably, this group has previously relied on malicious Excel documents to deliver .NET malware via ‘AppDomain Manager Injection’, specifically hijacking the same legitimate Windows binary, AppVStreamingUX.exe. Furthermore, the use of lures related to human rights violations in Iran aligns with their historical targeting patterns.

Despite these similarities, we cannot confidently attribute this activity to a single threat group at this time. Distinguishing between Iranian-nexus actors is increasingly challenging due to the communalities shared between them and the growing adoption of LLMs in attack campaigns. This has been reported in groups such as Crimson Sandstorm and across the broader Iranian APT landscape.

Additionally, the campaign infrastructure choices match other Iranian-nexus actors. For instance, the use of GitHub as a DDR by the “Drokbk” .NET malware used by the Iranian threat actor COBALT MIRAGE, while the use of Telegram for C2 has been reported in campaigns by separate Iranian threat clusters since 2022.

While we cannot pinpoint the exact Iranian subgroup, we attribute this activity to a Farsi-speaking threat actor aligned with Iranian state interests, with medium confidence. This assessment is based on the following attribution tokens:

- The presence of Farsi artifacts:

- One of the 7 Telegram accounts configured to operate the bot utilized Farsi as the account language;

- The malware developer’s GitHub account contained comments in Farsi (“‘ نمایش رشته نهایی در یک جعبه پیام”);

- The malware modules contained (likely AI-generated) comments in Farsi (“// پیشفرض 500MB”, “// 🚩 همه فایلها اضافه شد”, “// دیگه چیزی برای مصرف نیست”);

- The highly thematic alignment, using ‘shock lure’ discussing the civil protests in Iran aligns with the psychological warfare and surveillance objectives of the Iranian regime;

- The reliance on stolen/leaked email accounts, a tactic we previously reported in MuddyWater operations;

- TTPs similarities with IMPERIAL KITTEN outlined before.

Perhaps most peculiar is the tongue-in-cheek use of kittens imagery in the payload, suggesting a level of self-awareness in the “Kitten” naming convention.

Activity timeline

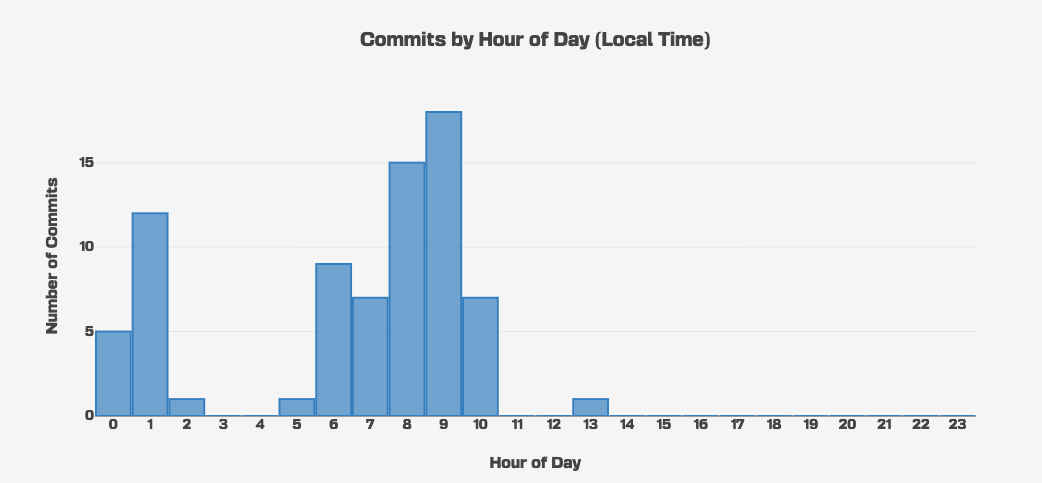

In addition to the assessment we previously outlined, we analyzed the malware author’s Git activity. The Git repository was setup to report US Pacific time UTC-7 (13 commits) and UTC-8 (63 commits) following the daylight saving time switch over:

commit b599a861230bc872316c38a03857e5e62f2bb518

Author: johnpeterson1304 <johnpeterson202024@proton.me>

Date: Sun Nov 2 06:14:22 2025 -0800

commit 57ebb18dc884db19a3471d7b8473fc315088a93e

Author: johnpeterson1304 <johnpeterson202024@proton.me>

Date: Mon Oct 27 08:14:11 2025 -0700Timelining the commits using these timezones, we obtain strange working hours:

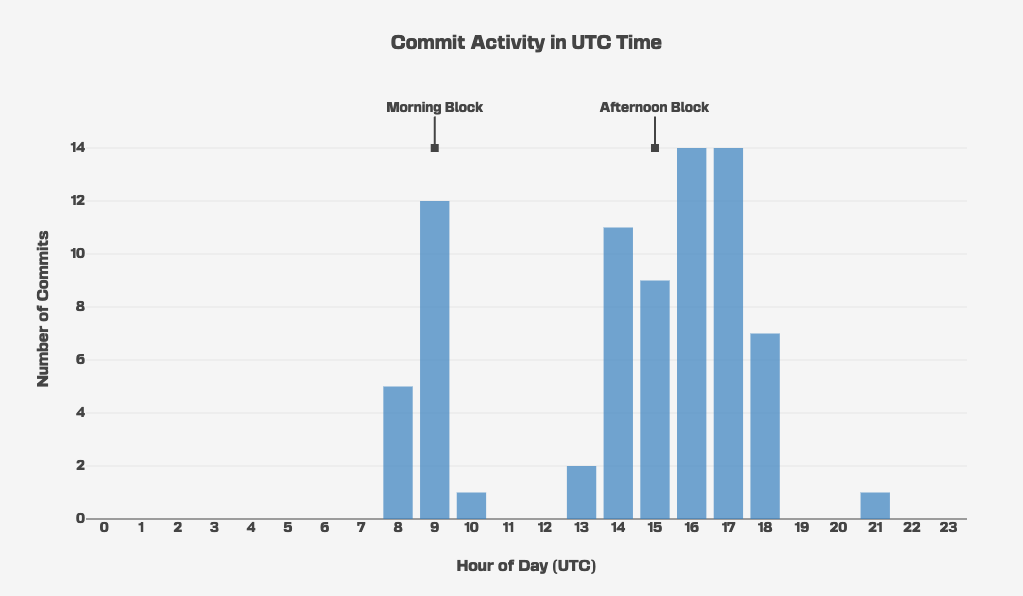

Shifting the commits hours to a more likely 9-5 hour spread, we observe a good match with the UTC/GMT timezone:

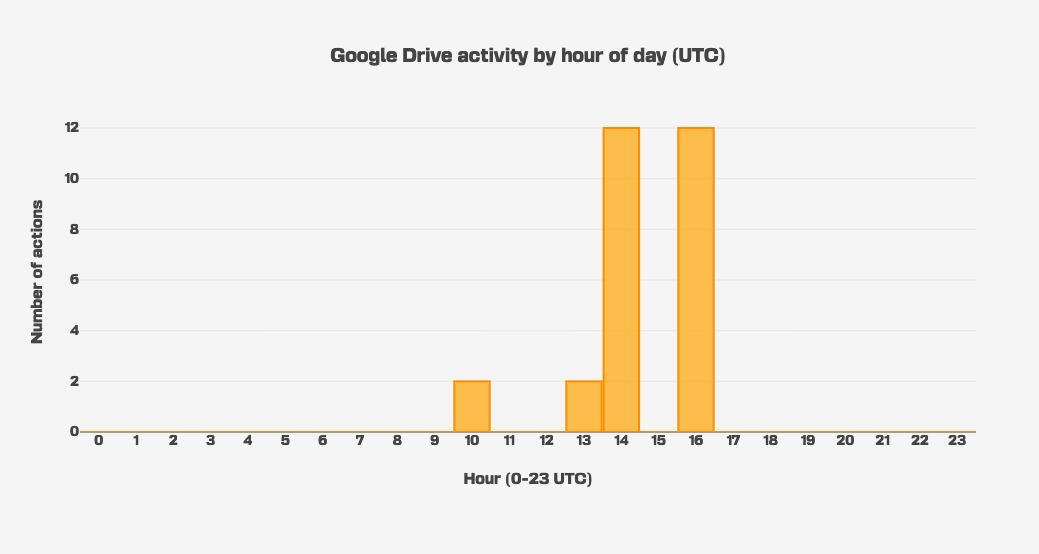

This hourly breakdown also fits the Google Drive files creation time:

We therefore assume that the malware developer(s) were operating around the GMT timezone.

Conclusion: letting AI do all the heavy lifting

RedKitten represents an AI-accelerated campaign that exploits the humanitarian crisis surrounding Iran’s Dey 1404 protests. While precise attribution remains difficult, similarities in Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs) as well as other artifacts we discovered clearly points to a Farsi-speaking threat actor aligned with Iranian state interests.

The threat actor’s reliance on commoditized infrastructure (GitHub, Google Drive and Telegram) hinders traditional infrastructure-based tracking but paradoxically exposes useful metadata and poses other operational security challenges to the threat actor.

Although AI tools likely enabled the malware developer to introduce support for modular implants and to incorporate capabilities like steganography, it could not compensate for an apparent hasty integration and lack of deep technical understanding. The reliance on generative AI is perhaps best exemplified by an unedited code comment found in one of the malware developer’s Gist: “ULTRA-RELIABLE & STEALTHY VBSCRIPT STAGER (Final Production Version)”. We leave it to the reader to imagine how the prompt for this response looked like.

Appendix: indicators and detection rules

Indicators of compromise (IOCs)

Associated IOCs are also available on our GitHub repository.

Hashes (SHA-256)

d3bb28307d11214867c570fe594f773ba90195ed22b834bad038b62bf75a4192|XLSM spreadsheet

c40c94d787f6a35ac1cb4c5f031cf5777b77c79dc3929181badea33aaf177aa7|XLSM spreadsheet

59ee007fd17280470724eb8a11ab12a98e85fd2383af3065f5f09a7e1a73f88c|XLSM spreadsheet

90aebc9849b659515fd70dde6db717ad457ab2a90522a410d1fd531ca8640624|XLSM spreadsheet

96ee9d3ed80c59c4bf39ed630efbfa53591fbe51155db7919ef64535a6171044|XLSM spreadsheet

6d474cf5aeb58a60f2f7c4d47143cc5a11a5c7f17a6b43263723d337231c3d60|SloppyMIO

16164c83ce4786ab85aa3fc9566a317519e866ff6cad3fbd647f3e955b8a8255|SloppyMIO

36413af1a7c7dc9e49fdf465ebc5abc3b4bb6b33f1c5ccaa17ae5e0794b6faaa|SloppyMIO

6e1bb2c41500ee18bd55a2de04bb3d74bd5c5e8c45eaeef030c7c6ea661cc2db|SloppyMIO

ac0e045b6f3683315ef420971f382e167385e39023d118d023fa6989e35fadf6|SloppyMIO

d58e3617d759d46248718ac4dfb46535d73febffd17fad1fd8ab47ce08da2fb4|SloppyMIO

e5c4295c5c57d80c875860b44f4c33ee921393bb8ce14c7be0f5ef47d7171265|SloppyMIOFile paths

%LOCALAPPDATA%\WindowsMediaSync\AppVStreamingUX_Multi_User.dll|SloppyMIOScheduled tasks names

^MediaSyncTask[1-9][0-9]{2}$|Initial execution (regular expression: MediaSyncTask followed by a number between 100 and 999)

Enterprise Workstation Health Monitoring|Scheduled task used for persistenceYARA rules

rule trr260101_sloppymio {

meta:

description = "Detects SloppyMIO, a C# implant leveraged by an Iranian threat actor in January 2026."

references = "TRR260101"

hash = "6d474cf5aeb58a60f2f7c4d47143cc5a11a5c7f17a6b43263723d337231c3d60"

date = "2026-01-28"

author = "HarfangLab"

context = "file"

strings:

$s1 = "AppVStreamingUXMainOff" fullword

$s2 = "Process exiting. Restart if allowed." wide fullword

$s3 = "[ errors in module '" wide fullword

$s4 = "[Error] Method '' not found in module '" wide fullword

$s5 = "href=[\"'](.*?/raw/.*?/" wide

$s6 = "FREE|" wide fullword

$s7 = "USED|" wide fullword

$s8 = "GET FAILED:" wide fullword

$s9 = "PATCH FAILED: " wide fullword

$s10 = "FILE NOT FOUND IN GIST" wide fullword

$s11 = "CONTENT FIELD NOT FOUND" wide fullword

$m1 = "StegoLsb" fullword

$m2 = "CachedModule" fullword

$m3 = "SystemEvents_SessionEnding" fullword

$m4 = "ExecuteCoreLogic" fullword

$m5 = "BuildInputParams" fullword

$m6 = "SendAsFileFromMemory" fullword

$m7 = "SendReplyInParts" fullword

$m8 = "ExecuteLib" fullword

$m9 = "ExecuteDirectModule" fullword

$m10 = "ExecuteModule" fullword

$m11 = "DownloadModuleCode" fullword

$m12 = "CompileDirectModuleCode" fullword

$m13 = "CompileModuleCode" fullword

$m14 = "GistRawLink" fullword

$m15 = "GetRemoteConfig" fullword

$m16 = "GetGistJson" fullword

$m17 = "UpdateGist" fullword

condition:

filesize < 100KB and

uint16be(0) == 0x4D5A and

(6 of ($s*) or (all of ($m*)))

}-

“Final List_Victims_D_1404_Tehran_Part One”, translated from Farsi. ↩

-

“Final list_victims_Dey_1404_Tehran_part two.xlsm”, translated from Farsi. ↩

-

“Final list_victims_Dey_1404_Tehran_part three.xlsm”, translated from Farsi. ↩

-

“Final list_victims_Dey_1404_Tehran_part five.xlsm”, translated from Farsi. ↩

-

“Final list_victims_Dey_1404_Tehran_part four.xlsm”, translated from Farsi. ↩